Solving Blind Spots in Wildfire Emergency Planning

RWI understands the complex dangers posed by wildfires better than most. Our headquarters is in Alberta, a western Canadian province where summer wildfires are now both an acute and chronic issue. But the number of wildfires across North America and around the world has increased dramatically over the past few years.

The social, economic, and human costs are matched only by the complexities of addressing preparedness in the face of an unprecedented new normal.

A variety of both private and public organizations have attempted to report on, diagnose, and make recommendations to see, solve, and operationalize upon these complexities; most recently, with the “Canada’s Wildfire Blind Spot: The Missing Data on Social Impacts” report, released by the Canadian Red Cross and the Conference Board of Canada.

The Blind Spot report makes key recommendations and observations about data silos and the improper frameworks used to assess wildfire impacts in Canada, and suggests methods to increase and harness collaboration between communities and levels of government.

Several of these recommendations, however, were made several years ago in the 2023 First Nations Strategy and miss the opportunity to embrace the “all-of-society” approach outlined in that same strategy.

Finally, RWI has already created and continues to apply our collaborative, high-fidelity platform for emergency management and response, using people-centered Synthetic Intelligence to ensure humanity, collaboration, and the navigation of complexity remain at the heart of the conversation.

Canada’s Wildfire Blind Spot

The Blind Spot report begins with an analysis of the nation’s current wildfire reporting methods, noting that although Canada does well at collecting data on the physical and resource impacts of wildfires, the social impacts are often underreported or left out of the conversation entirely.

“Emergency management organizations (EMOs) track the land burned, number of buildings lost, and firefighting resources allocated during a season. In comparison, it is harder to measure mental health indicators, community cohesion, loss of cultural artefacts, and traditional ways of life in concrete terms.”

The report cites several reasons for this: social impacts unfold over a longer period of time than immediate physical impacts, policies that address social impacts tend to emerge more slowly, and due to wildfires occurring far from Canada’s most populous urban centers, “these events can fail to capture the broader public’s imagination.”

Efforts to capture data around social impacts exist at the municipal and NGO levels, but they are siloed, inconsistently supported, and hampered by poor collaboration and unclear ownership.

The Blind Spot report recommends establishing a “national database of disaster impacts” that integrates data from a broad range of relevant organizations and sources.

“Municipalities could leverage their direct connection with communities and non-governmental organizations, and are also well-suited to capture socio-economic vulnerabilities that may be overlooked by higher-level agencies. Ensuring effective and consistent tracking of this information would require municipalities to take on added responsibilities. This would necessitate increased financial outlays and additional support from provincial–territorial and federal governments.”

The overall goal would be to operationalize this data to guide policy and resource allocation, leading to both better immediate outcomes and greater long-term resilience for communities affected by wildfires.

The Goals of the First Nations Fire Protection Strategy

While the Blind Spot report’s recommendations seem practical and innovative for increasing collaboration and defining inter-agency frameworks, the Canadian First Nations Fire Protection Strategy (FNFPS) offers an overlapping and distinct approach to engaging in that collaboration and was released over two years earlier.

The two sections where First Nations and Indigenous groups are mentioned are as follows:

“First Nations could report the social impacts of wildfires to Indigenous Services Canada, while Inuit and Métis communities could report them to their respective provincial–territorial emergency management agencies… Indigenous communities must be engaged in a way that acknowledges their unique status and needs.”

Knowledge sharing was a core goal of the 2023 FNFPS. In addition, the Blind Spot report makes no mention of who would be involved in developing these policies after data allocation or how Indigenous data sovereignty would be respected.

Although the report states that “social impact data could be used by policy‑makers to both plan and prioritize the allocation of resources to recovery efforts,” in the developed framework they offer in Fig. 1, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities only provide information in a singular direction, and it is unclear what they receive in return.

While collaboration, inter-agency, and inter-governmental sharing are vital tools in emergency management, they must be conducted equitably. Key elements of the FNFPS are formed by the UN SENDAI, or “all-of-society,” framework, which emphasizes “inclusive engagement of governments, civil society, private sector, and vulnerable groups … to reduce disaster risk and build resilience, recognizing it as a shared responsibility for sustainable development, integrated into policies and daily actions across all sectors.”

In this way, equitable collaboration and policy development that respect the agency of the communities they aim to serve are not only the just option but also a strategic one.

In Lisa Armstrong’s “From Risk to Resilience,” she writes that including local perspectives, assets, and intelligence has an exponential effect on community resilience, leveraging unique community assets to address the problems they face.

“These kinds of local resources are not always captured in formal emergency plans, but they are vital and can be mapped and shared locally and regionally,” Armstrong writes. “By making these community assets visible and accessible, emergency planners can strengthen local response and recovery capacity.”

A Platform For Everyone

Both the Blind Spot report and the FNFPS agree that de-siloing is a vital aspect for effectively responding to the future of emergency management, and it is a problem we’ve already solved.

RWI’s platform is the ideal tool to ensure the invisible becomes visible, and we understand that collaboration and accessibility are not just features but are essential to the success of strategic problem-solving and resilience-building.

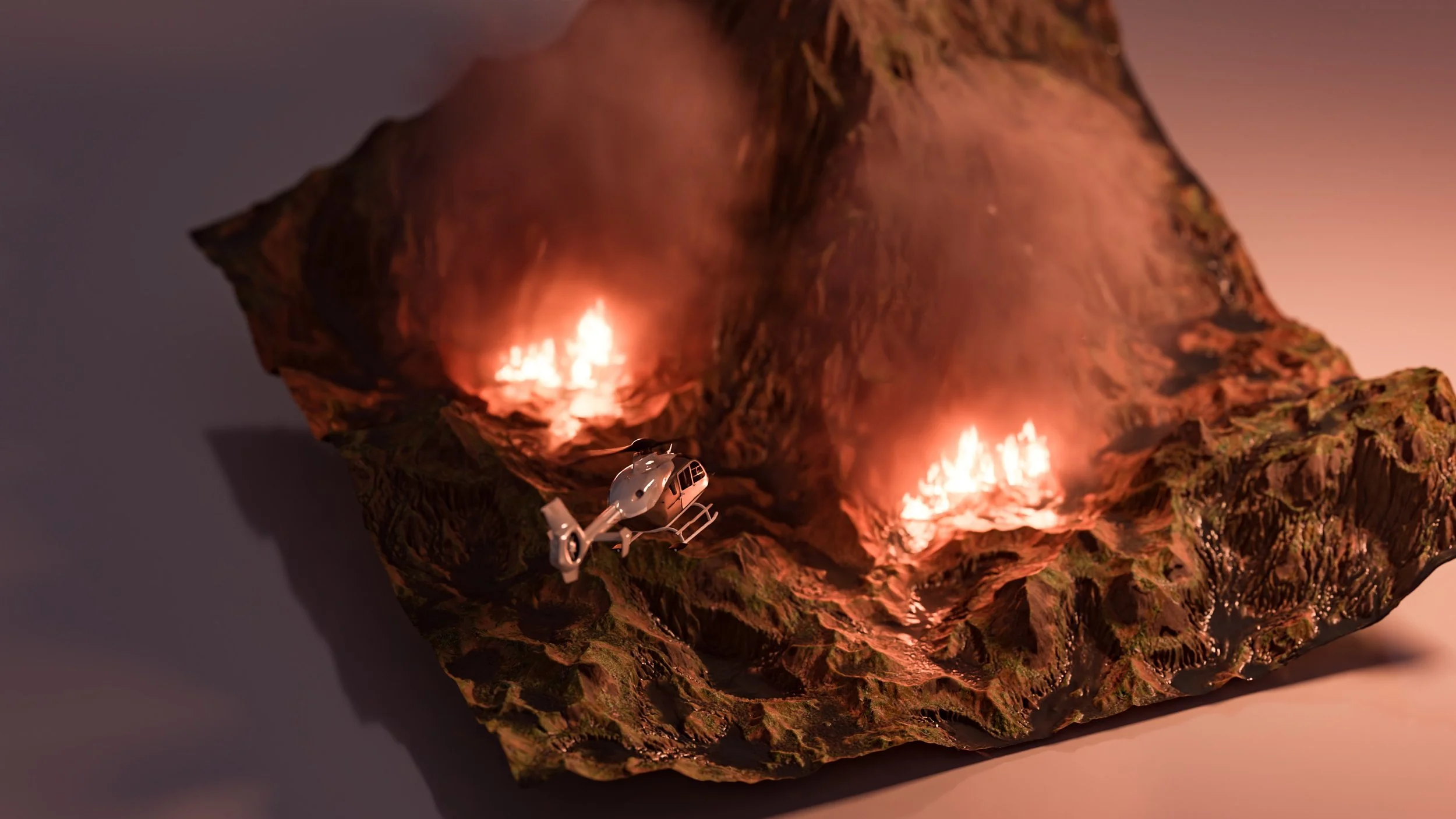

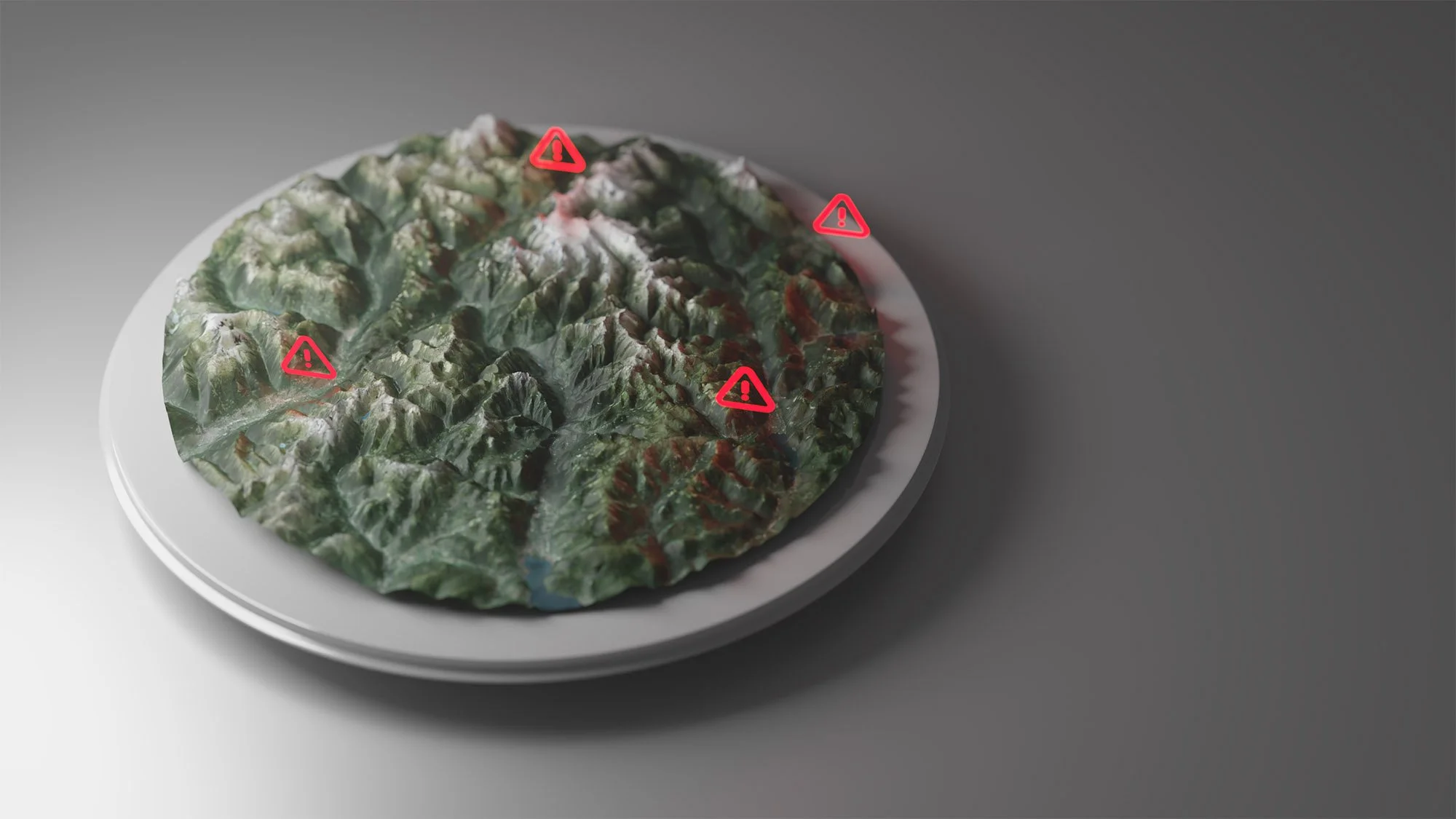

Our web-based, 6D visual shared interface lets users directly manipulate key variables and scenarios to forecast everything, including unprecedented futures: whether it’s quantifying the invisible dangers of wildfire smoke, geolocating where to place air quality sensors to protect the most vulnerable populations, or using Synthetic Populations to model fire egress methods to inform infrastructure decisions.

These innovations bring complex-scenario sandboxing to an accessible platform where participants can create and modify simulation parameters, configure context, and observe outcomes in a virtual, geospatially accurate world.

This provides the unique capacity to de-silo subject matter, data, and expertise, bringing them together in a converged space focused on consensus building, collaboration, and understanding.

Our platform has already undergone testing through a contract with the Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada Innovation Solutions Canada program (ISC), and has even been utilized for reconstruction efforts and visualization following the L.A. wildfires in 2025.

By combining interactive visualization, datasets, and local expertise, and by including decision-makers within a single, collaborative environment, our platform enables organizations to move beyond reactive responses toward proactive resilience. The result is not only clearer visibility into emerging risks, but faster alignment, better decisions, and outcomes that protect communities when it matters most.

Conclusion

Wildfires are no longer isolated events or seasonal anomalies; they are a defining feature of a rapidly changing risk landscape that demands new ways of seeing, solving, and operationalizing. As the Blind Spot report and the FNFPS both make clear, the challenge is not a lack of data or a lack of desire for collaboration, but the persistent fragmentation of knowledge and equitable frameworks.

Wildfire preparedness and recovery require shared understanding and tools that can translate complexity into coordinated action.

RWI’s platform directly addresses this gap. By making social, environmental, and infrastructural impacts visible within a single, people-centered environment, it respects agency, supports decision-making, de-siloes intelligence, and understands the importance of information sharing between all four orders of government, non-profit agencies, and private business.